From the early days of the Wild West until the turn of the 20th century, yellowfin and greenback cutthroat trout coexisted in Rocky Mountain alpine lakes. Larger than greenback cutthroat trout, the yellowfin cutthroat trout was a beast weighing up to 12 pounds and distinguished by its bright yellow fins.

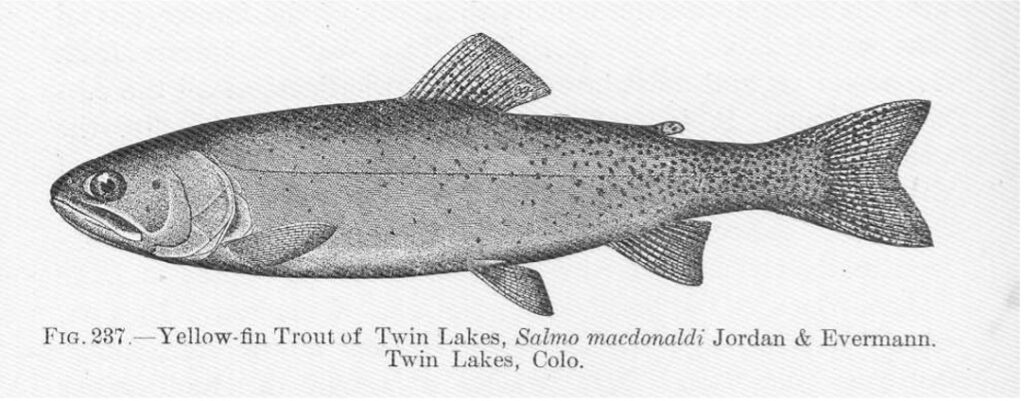

This remarkable fish was discovered in 1889 by ichthyologists when they conducted a survey of Twin Lakes, two lakes on a tributary of the Arkansas River near Leadville, Colorado. Proclaiming this new species the yellowfin cutthroat trout (Oncorhynchus clarkii macdonaldi) in the 1891 United States Fish Commission Bulletin. They described the fish as silvery olive in color, with a broad lemon-yellow shade along the sides and lower fins that was bright yellow in life, with a deep red dash on either side of the throat.

Until about 1902, yellowfin and greenback cutthroat survived in Twin Lakes, although populations remained isolated. When rainbow trout was introduced to Twin Lakes, this had devastating consequences for the yellowfin. While the greenback population interbred with rainbow trout, creating the new “cutbow” hybrid, the yellowfin disappeared, and is widely believed to be extinct.

However, fast-forward to 2022, and biologists in Colorado are on a quest to find what has been coined a “zombie fish.” Despite the species vanishing more than 120 years ago, wildlife officials contend that this giant among cutthroat trout might still exist in isolated pockets, somewhere in the waterways of Colorado.

Gone for good, or just hidden?

Other fish species previously presumed extinct have reappeared across the state, with the greenback cutthroat trout—Colorado’s state fish—rediscovered a decade ago. Eight small, previously unknown populations of San Juan River cutthroat trout were found in 2018.

Experts content that it is entirely feasible that the fabled yellowfin could still be in hiding somewhere in Colorado, with a July 2022 press release from wildlife officials announcing that while it may be a longshot, state aquatic biologists are searching for signs of the species.

As covered by the Sacramento Bee, biologists Paul Foutz and Alex Townsend are leading a Colorado Parks and Wildlife team on the painstaking search, scouring streams, wetlands, and ponds in search of the fish. They’re gambling on uncovering a hidden yellowfin population, inspired by the 2012 rediscovery of about 750 greenback cutthroat trout in Bear Creek near Colorado Springs—a find that stunned and delighted Colorado’s fishing community, scientists, and conservationists alike.

Foutz, Townsend, and their team intend to use genetic testing and other modern technologies to help track down and identify the fish. The team started sampling “all potential waters” in June 2022, with the intention of continuing their analysis every summer through 2025.

Speaking to the Bee, aquatic biologist Greg Policky cited the project as an exciting opportunity to explore Colorado’s unchartered waters in search of the yellowfin cutthroat, adding that he had dedicated most of his career to learning everything possible about the elusive species.

Co-leading the project, Foutz is the senior fisheries biologist for the CPW’s southeast region. He told the press that his team is going into the search with their eyes wide open, knowing the history of the yellowfin and that it has not been documented since before 1902. However, as Foutz points out, millions of trout, both nonnative and native, have traversed the waterways of the state, even before the species was identified in the late 1800s.

On a quest through Colorado and beyond

The Smithsonian Museum of Natural History has proved a vital resource for the search team: the museum still maintains five of the seven specimens of yellowfin collected and preserved during the survey of Twin Lakes in the late 1880s. These 130-year-old specimens contain genetic data that can be used to match wild yellowfins found in Colorado’s backcountry. The genetic data could also help restore the population.

The team’s search is not confined to the creeks, ponds, and springs around Leadville, where the species was last documented. In fact, the Leadville National Fish Hatchery propagated millions of trout over the years, including yellowfin, with specimens sent far and wide across the state and beyond.

Just as biologists rediscovered the greenback beyond its native range, so it is also possible that the yellowfin cutthroat trout could pop up somewhere they were sent more than a century ago. The fish hatchery’s historical records could provide vital clues, helping the team to identify potential areas where pockets of yellowfins could persist, unnoticed by CPW officials. In fact, according to the autobiography of one of the scientists that originally identified the yellowfin trout, the Leadville hatchery shipped yellowfin eggs all the way to France.

However, Foutz and Townsend told the press that they intend to start their search much closer to home. A 2020 survey suggests that 236 Colorado waterways have no stocking data, meaning that no fish species were ever planted there. As Townsend explains, although yellowfin cutthroats are no longer present in Twin Lakes, it is still possible that a remnant population with pure genetics could be tracked down to high mountain lakes, drainages, and tributaries in the area. Although it has been more than 100 years since the yellowfin was last documented, the team remains hopeful of rediscovering a remnant population of one of Colorado’s four endemic cutthroat trout subspecies.